“The earliest experience of art must have been that it was incantatory, magical; art was an instrument of ritual.”

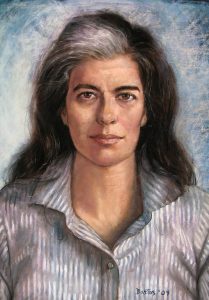

The Observer (sister paper of The Guardian) has been running a series – the 100 Best Nonfiction Books of All Time – and at number 16 they have Susan Sontag’s 1966 work ‘Against Interpretation.‘ [footnote]The article’s headline focuses on that one essay, which was in fact part of a collection of essays called Against Interpretation and Other Essays [/footnote]

One unlucky (but hugely experienced) journalist was given the task of reviewing the ‘book’ which is in fact an essay, all of eight pages long, and which argues passionately against the review, or at least interpretation, of works of art. By which Sontag meant attempts to impose or explain meaning:

“Interpretation, based on the highly dubious theory that a work of art is composed of items of content, violates art. It makes art into an article for use, for arrangement into a mental scheme of categories.”

“It is always the case that interpretation of this type indicates a dissatisfaction (conscious or unconscious) with the work, a wish to replace it by something else.”

So, writing a review of the polemic against explanatory reviews was, in many ways, a thankless task. The journalist skirted the issue by barely referring to the essay, at all, but focusing more on Sontag’s life, her other works and in particular another essay entirely.[footnote] Even the ‘signature sentence’ comes from another essay, ‘Camp’, not ‘Against Interpretation’. [/footnote] Which is a shame, because ‘Against Interpretation’ is a great read:

In most modern instances, interpretation amounts to the philistine refusal to leave the work of art alone. Real art has the capacity to make us nervous. By reducing the work of art to its content and then interpreting that, one tames the work of art. Interpretation makes art manageable, comformable.

This philistinism of interpretation is more rife in literature than in any other art. For decades now, literary critics have understood it to be their task to translate the elements of the poem or play or novel or story into something else.

I can understand why the journalist shied away from trying to paraphrase the meaning of ‘Against Interpretation.’ I really, really can. What I can’t understand is why the writer didn’t simply let Sontag’s words stand for themselves, by quoting them. Words such as these:

Ours is a culture based on excess, on overproduction; the result is a steady loss of sharpness in our sensory experience. All the conditions of modern life – its material plenitude, its sheer crowdedness – conjoin to dull our sensory faculties. And it is in the light of the condition of our senses, our capacities (rather than those of another age), that the task of the critic must be assessed.

What is important now is to recover our senses. We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more.

Our task is not to find the maximum amount of content in a work of art, much less to squeeze more content out of the work than is already there. Our task is to cut back content so that we can see the thing at all. The aim of all commentary on art now should be to make works of art – and, by analogy, our own experience – more, rather than less, real to us. The function of criticism should be to show how it is what it is, even that it is what it is, rather than to show what it means.

Sontag is urging us not to sit around in an intellectual pose saying clever things about art (books, movies, whatever) in the hope you’ll look smart. Throw yourself into the experience. Art is reality. Art is real. If it wasn’t, it wouldn’t be there.

It is an empowering and joyous message: it is better to read a book and enjoy it, than to blather hot air about its meaning.